“Let us not kid ourselves, Russia is now the most influential player in the region, and that is mostly due to Obama’s doctrine….which saw the U.S. role shrink.” (Faisal Abbas on RT)

“Media Exchange Between Russia and Saudi Arabia.” Source: Sputnik, October 10, 2017. Photo: Vladimir Medinsky, Minister of Culture of the Russian Federation (Left) and Saudi Culture Minister Awaad al-Awaad

By Elliot Stewart

The now well-understood efforts by Russia to influence public opinion and political processes in the West rely on a wide set of tools – from social media bots, to cyberattacks, to “astroturf”political organizing. But the Kremlin’s most visible tools of influence are its state-controlled media outlets.

These outlets, led by RT (formerly Russia Today), have made headlines for their efforts to sow mistrust in democratic institutions and spread fodder for conspiracy theories in the West. The Kremlin’s media project is global, however, with the self-stated goal “to break the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on the global information streams” and forge a more pro-Russian world.

Outside the West, this global project has focused most robustly – and has been most successful – in the Middle East, where RT Arabic is now one of the most popular news sources.

The rising popularity of Kremlin media in the Middle East has gone hand-in-hand with increasing Russian military and economic influence, as regional states, including U.S. allies, react to signs of an impending U.S. withdrawal from the region.

A NEW ERA OF JOURNALISM

The Kremlin’s global media ambitions were on full display in June 2016, when Rossiya Segodnya [Russia Today, the state holding company for RT and other publications–The Interpreter] hosted an ostentatious event billed as the New Era of Journalism: Farewell to Mainstream. Unabashedly, the event was planned to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the creation of Rossiya Segodnya’s precursor, the Sovinformburo(Soviet Information Bureau).

Photo source: Sputnik, July 7, 2016

While much of the conference seemed focused on sending a message to the West — including attacks on Google and Hillary Clinton delivered remotely by Julian Assange – the conference’s list of panelists reflected the Kremlin’s broader set of priorities, boasting state media representatives from China, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Lebanon, Greece and Serbia, as well as an American journalist who was a staunch supporter of Hugo Chavez.

Representing the largest regional contingent of panelists were the heads of some of the Middle East’s most influential state-owned news outlets: Faisal Abbas, tasked with heading a modernizing overhaul of Saudi Arabia’s state-owned media organs; Ahmed Dawa, the director general of Bashar al-Assad’s primary propaganda organ, the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA); and Ghassan ben Jeddou, chairman of the pro-Assad and pro-Hezbollah Al Mayadeen TV.

Together, Dawa and Jeddou represented the ‘Axis of Resistance‘ – the self-styled alliance among Iran, Hezbollah and Bashar Al-Assad to counter Western influence – and seemed natural invitees to the event. But Abbas, a rising figure in mainstream Sunni media that strongly opposes Iranian influence in the region, was less obvious. Nevertheless, all three were drawn by the same goal: improving relations with the increasingly assertive President Putin and his state-owned media.

The attendance of these three officials was a product of more than a decade of Kremlin investment in the Middle East. From the inception of RT in 2005, Arabic-language messaging has been a core priority – RT Arabic was the first channel launched after RT International (which broadcasts in English) and preceded the launch of channels in Spanish, German, and French by several years.

Rossiya Segodnya, the Kremlin’s newest media conglomerate and host of the June 2016 conference, has similar priorities in mind. Sputnik, its foreign news service, produces the majority of its content in English and Arabic.

Source: RIA Novosti

LIKE-MINDED PARTNERS

The attendance of state media

officials from both sides of the region’s deep political and religious divides

says much about Russia’s appeal as a rising power in the region. As in the

West, RT has benefited from the Middle East’s political polarization.

Dr. Naila Hamdy, an associate

professor of journalism and mass communication at the American University in

Cairo, noted how “RT may have filled up that gap” left in Egypt and the

wider region following the Arab Spring, when an increasing number of viewers began

to see Al-Jazeera as closely affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood and

other Islamist parties.

This increasing regional

polarization erupted in the summer of 2017 with the Saudi-led embargo of Qatar,

with Saudi and its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) partners demanding

the closure of Al Jazeera as punishment for Qatar’s alleged support for the

Brotherhood, as well as Iran and its regional Shiite proxies.

Remarkably, even as Russia has

worked closely with both Iran and Hezbollah to rescue Bashar Al-Assad from near

defeat in Syria, its state-run media have been met with minimal resistance from

regional governments, including U.S. allies Saudi Arabia and the United Arab

Emirates. Beyond a brief

blocking of Sputnik‘s website in Turkey in a tit-for-tat

row, Kremlin media targeting Middle East audiences continues to operate

virtually unchecked.

This stands in contrast with the

West, where, despite notable

disinterest from the Trump administration, the collective weight of

revelations regarding Moscow’s influence has resulted in some significant

countermeasures against Kremlin media: Russian state-owned outlets have been

banned from advertising on major social media networks, forced to register as

foreign agents in the United States, removed from

D.C.-area broadcasts, targeted by British media watchdog investigations, and

even banned

outright from Ukrainian telecommunications networks.

In even starker contrast, government-owned

outlets in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Algeria, as well as Saudi Arabia

and the United Arab Emirates, have all signed deals to cooperate with Kremlin outlets.

During the June 2016 conference in

Moscow, SANA‘s Ahmed Dawa and Al-Mayadeen‘s Ghassan ben Jeddou,

regional allies of Russia’s project to save the Assad regime in Syria, were

invited on stage to

sign media cooperation deals with the Kremlin’s “chief

propagandist” and the head of Rossiya Segodnya, Dmitry

Kiselyov.

As with the SANA and Al-Mayadeen

deals, the motivation behind other regional agreements has often been

spurred by shared anti-Western ideology, perhaps most notably with Iranian

propaganda outlets, but also with state-affiliated outlets

of Egypt. Alaa Abdel Hadi, editor-in-chief of Egyptian state-owned Akhbar Al

Yom, explicitly heralded

closer cooperation with Russian media as a counter to Western media hegemony:

“For a long time the West controlled the media, so today we are happy to

cooperate with the Sputnik agency, which will help us see other aspects of the

truth.”

Part of a common regional theme, the

Kremlin’s media deal-making has often been facilitated by guns and oil. Deals

signed with Algeria,

as well as traditional U.S. allies Saudi Arabia and the United

Arab Emirates, were accompanied by millions of dollars in arms

and oil deals.

The attendance of Saudi Arabia’s

Faisal Abbas at the June 2016 Moscow media conference was a striking acknowledgement

of the temptation Russia’s growing military and economic influence poses for

traditionally staunch U.S. allies as U.S. influence appears to be receding. His

presence was also revealing of the close relationship between media and

national security officials in both Russia and many regional states.

A year after the Moscow conference,

Saudi King Salman became the first Saudi monarch to visit Russia, where he met

with President Putin. During the visit, billions of dollars’ worth of military

and economic deals were signed between the two nations. The scale of the

agreements sent reverberations throughout the West, with The Guardian

describing the deals as a “shift

in global power structures.”

Amid the hubbub of the Saudi-Russia summit,

Anton Ansimov, head of International Broadcasting for Sputnik and

moderator at Abbas’s June 2016 panel discussion, signed

a letter of intent for “professional cooperation” with the Saudi

Minister of Culture and Information, Awaad Al-Awaad.

Acting less as an editor-in-chief

than as a representative of the Saudi Crown, Faisal Abbas appeared on

RT to praise the King’s visit, stating bluntly: “Let us not kid

ourselves, Russia is now the most influential player in the region, and that is

mostly due to Obama’s doctrine….which saw the U.S. role shrink.”

In an interview

with RT, Al-Awwad expressed the ways in which greater media

cooperation with Russia could also provide a united front against terrorist

organizations and support provided to them by Qatar and its state-funded media

outlet Al-Jazeera.

A similar deal with the official

news agency of the United Arab Emirates, WAM, provides a particularly illustrative

example of how Russia’s rising economic and military influence vis-a-vis the

United States has created divergent attitudes toward Kremlin media among

Western actors and their traditional Gulf allies.

Less than two weeks after RIA Global

LLC, which produces content for Sputnik in the U.S., was

compelled to register

under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), WAM signed

a memorandum of cooperation with RT. The media agreement was preceded by

a February 2017 purchase of Russian fighter aircraft that the National

Interest described

as “an indication that the UAE—a long-time U.S. ally—is drifting into

Moscow’s orbit.” The signing was followed in June 2018 by the signing of

a “strategic partnership” between Vladimir Putin and Abu Dhabi Crown

Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed aimed at “providing balance and stability

on the global oil market.”

But media cooperation between the official outlets of

Russia and Middle East states is more than an afterthought of arms and oil

deals. In both Russia and the Middle East, media outlets are commonly

understood as tools of authoritarian rule, creating a number of incentives for

cooperation.

In an interview conducted for this article, Rana Sabbagh, the executive

director of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) bemoaned the strangle-hold of

regional government over the region’s most influential outlets: “Everyone

is on the payroll of their government, so everyone is a parrot to what their

government wants.” Her organization, funded by the Norwegian and Dutch foreign

ministries, works to promote “the

hitherto unknown culture of accountable journalism,” and is one of

very few regional exceptions that prove the authoritarian rule.

And according to

Sabbagh, censorship and intimidation of journalists in the region is only

increasing: “I’ve been in the business for thirty-five

years…and the last three years have been crippling.” She described

existing laws to protect journalists on the books in many regional states as

“window-dressing” designed to check the boxes of Western donors, but

which have little to no real-world impact given overriding counter-terror and

cybercrime laws: “The government can turn you into a terrorist…just if

you publish something or re-tweet something they don’t like.”

Regional journalists

interviewed for this article further elaborated on background that in many

regional countries, state intelligence agencies play a heavy role in media

affairs, and in effect have the power to approve or dismiss editors.

Western news outlets, which often

engage in investigative approaches to journalism, pose a threat to the tight grip

regional governments have on media in their countries. Russia’s brand of

statist media thus offers Middle East autocrats, including U.S. allies, with a comfortable “alternative”

foreign news source. The Kremlin’s approach to journalism, which eschews

coverage of human rights abuses, corruption or other unwanted stories at

home, is unlikely to expose similar abuses by its partners abroad.

Managing Director of RT Alexey Nikolov and Peyman Jebelli, head of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) organization, sign a media cooperation agreement in Tehran in March 2018. Nikolov claimed: “Russia’s RT and Iran’s Press TV share a similar mission and vision. The two channels are seeking to cover world events from a different perspective, different from that of the Western media.” Source: Fars News

Media cooperation between Russia and the Saudi kingdom continues to develop with these “mutual interests in mind,” with a Russian delegation traveling to Riyadh in January 2018 to discusses “cultural and media cooperation” with Al-Awwad, and Al-Awwad traveling to Moscow in July 2018 to meet with his Russian counterpart Konstantin Noskov to discuss “further strengthening of media interaction, boosting investment mechanism in various media outlets so as to effectively use the media content to serve issues of mutual interest.”

In August, Sputnik Arabic noted how a meeting between Al-Awwad and Sergei Kozlov, the Russian Ambassador to Saudi Arabia, “came in the days following Russia’s affirmation of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign right to deal with matters related to human rights following Canada’s criticisms of Saudi Arabia related to the arrest of activists in civil society.”

This ability to rely on supportive messaging from foreign outlets is a clear benefit of close relations between state-owned media. Breaking the “Anglo-Saxon monopoly” on global media is useful for like-minded autocrats the world over.

Perhaps the most ambitious aspect of the Kremlin’s global media project is not to provide alternative news coverage of events to that of “Anglo-Saxon” competitors, but to harness a more fundamental strata of information by restructuring the bedrock institutions of international journalism.

The Kremlin has invested heavily in providing an alternative to the Western newswire services (Reuters, Agence France Press, and The Associated Press), relied on frequently by both international giants and hundreds of smaller international news organizations to gather primary reporting and provide content to fill broadcasts.

Adding to the newswire service offered by Sputnik, RT launched the “full service global video news agency” RUPTLY in 2013. Providing the rationale behind the new agency, Margarita Simonyan claimed that “basically a handful of agencies…provide [the] majority of news footage to international outlets, and particularly to TV channels and online platforms that cannot afford to have bureaus or send correspondents to every hotspot.” According to her, this means that “viewers often see events around the globe through the eyes of these providers,” and that “there are inevitable gaps in coverage, plus the risk of bias in the eventual reportage…”

But providing alternatives to these agencies, widely regarded as professional and independent, also provides a means to circumvent the kind of independent reporting that can give Kremlin propagandists headaches. In attempting to obscure the Bashar al-Assad regime’s culpability in civilian deaths in Syria, the Kremlin’s outlets often relied on content from RUPTLYand Sputnik to challenge and attempt to discredit widely-cited reports provided by independent agencies.

So even as RT Arabic has risen to become one of the region’s most influential spin rooms, the Kremlin would also like to erode this deeper, inbuilt resistance to its worldview. In Simonyan’s words, “RT has already established itself as the alternative voice on the international news landscape and now, with RUPTLY, we can bring our vision and expertise to a whole new market.”

In addition to offering similar stock footage and rent-a-crew services like other newswires, RUPTLY has embraced disruptive technologies as a way of gaining an advantage over local news channels, allowing anyone with its mobile application, described as a “citizen journalism platform,” to stream live video and to earn money by fulfilling “specific tasks.”

One former employee, who continues to view Kremlin media as a “necessary” evil, has publicly attested to RUPTLY’s overtly political agenda and poor journalistic standards.

In September 2017, RT Arabic launched a RUPTLY-style platform specifically for Arabic speakers dubbed RT Online, which purports to be “the first live news enterprise on social media” that allows users to “participate in news broadcasts in real time and discuss on air the events they witness.”

More than just additional channels on regional satellites, the Kremlin is offering a holistic alternative to rigorous, independent international journalism from the ground up. This explicitly anti-Western alternative aims to bring about the “New Era of Journalism” for which the Kremlin positioned itself as leader during the June 2016 conference in Moscow.

Like its channels in the West, the Kremlin’s Arabic-language outlets exploit existing grievances to Russia’s advantage. In the words of one regional journalist, “They are focusing on the things that America is lying about the world, so they have a kind of credibility to the public.”

“The International Coalition Moves Daesh Leaders to Unknown Destination” Source: Sputnik, September 22, 2018.

Articles and videos published by Kremlin outlets frequently provide fodder for already wide-spread anti-Western conspiracies – including that the U.S. supports terrorist groups, and that Western government have helped staged false-flag chemical weapons attacks on civilians to justify greater Western military intervention.

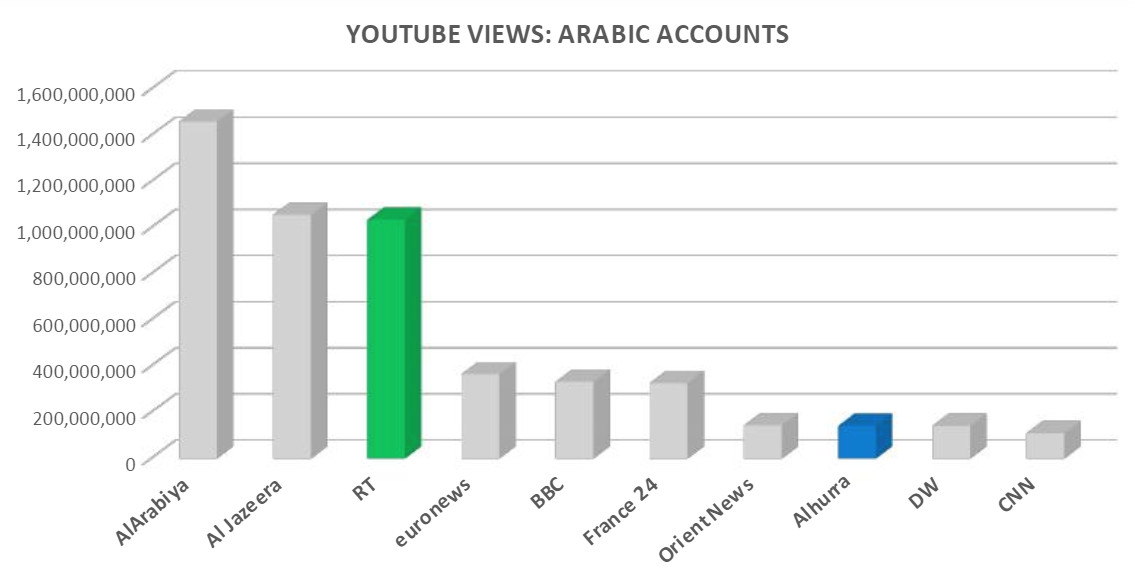

But unlike RT‘s channels in the West, which some argue remain marginal sources of news, a broad set of metrics strongly suggest RT Arabic has made staggering gains over the past decade to become one of the most widely-consumed news sources in the Middle East.

As of 2014, RT Arabic became one of the top three most-viewed TV channels in the Middle East according to a Nielsen study commissioned by RT, with higher daily viewership in six major Middle East countries than BBC Arabic, Sky News Arabia, the U.S. government-funded Alhurra and China’s CCTV in Arabic. RT was beaten out only by regional heavyweights Al Jazeera and AlArabiya. RT also boasted in 2015 that it had become “the world leader among non-Anglo-Saxon international TV news channels,” based on data provided by comScore, an America media measurement and analytics company.

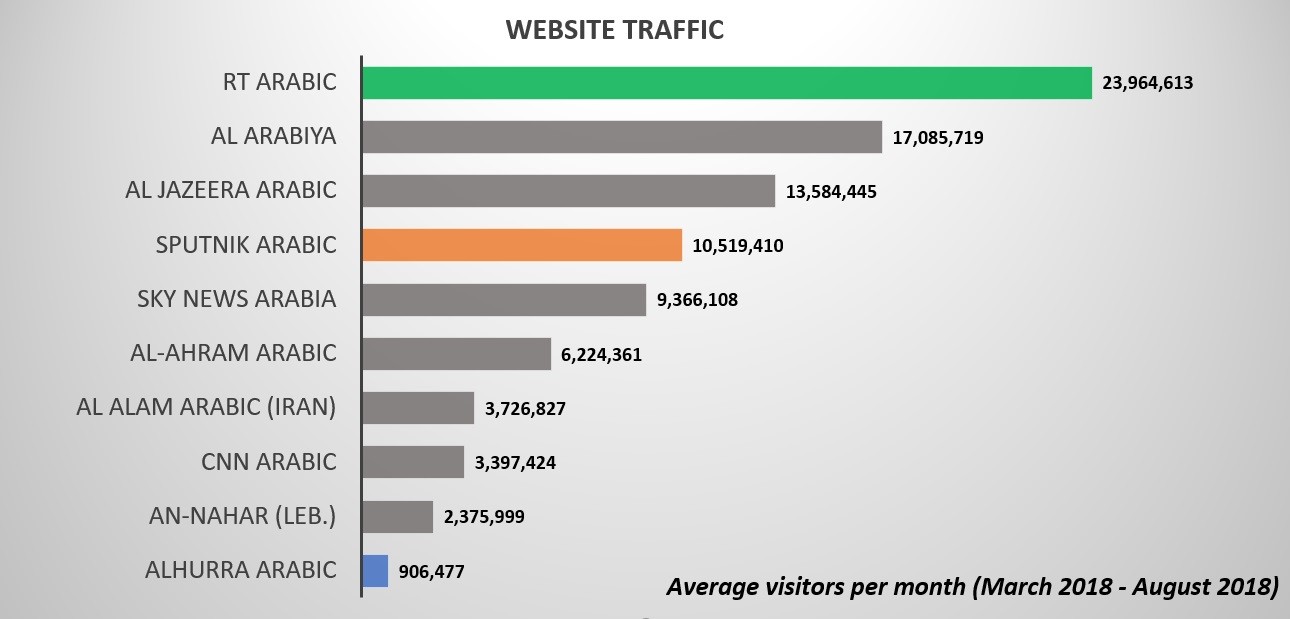

Most recently, RT announced in August 2018 that it had become the number one Arabic-language news portal, handily beating out not just international contenders like CNN, but also outpacing Al Jazeera and AlArabiya, according to SimilarWeb data. Notably, SimilarWeb’s publicly available data suggests even Sputnik, the Kremlin’s much smaller but even more inflammatory mouthpiece, is now garnering nearly two-thirds of Al-Jazeera‘s online traffic in Arabic.

Source: SimilarWeb.com

Western analysts and commentators have justifiably expressed doubt about the reliability of RT‘s self-commissioned audience studies. A number of observers have also noted the often trivial content that has propelled RT (English) to become the most watched news network on Youtube; an internal RIA Novosti report compiled in 2013 and leaked to The Daily Beastpointed out that many of the outlet’s most-watched videos are related to “natural disasters, accidents, crime, and natural phenomenon” rather than content that advances a pro-Kremlin worldview.

But while these arguments raise legitimate questions about RT‘s influence in the West, RT‘s success in the Middle East is much harder to refute. RT Arabic’s claim to be the leading Arabic-language news portal is based on publicly available, independent data, rather than studies commissioned by Russian media.

Moreover, the popularity of RT Arabic‘s Youtube channel, which has nearly two million subscribers and more than one billion views (making it the only non-Arab news channel competing with regional leaders Al Jazeera and AlArabiya), is not driven by the same frivolous style of content as RT’s English Youtube channel.

Many of RT Arabic‘s top 100 most-watched videos on Youtube, all of which have received more than one million views, consistently promote Russian military prowess, cover military and counter-terror developments in the region, portray Vladimir Putin as a strong leader, and criticize the history of U.S. involvement in the region. Frivolous content is still present, but far from the rule among these most-watched videos.

Coinciding with the rise of Kremlin media is a more fundamental shift in regional opinion, where for the first time a majority of young Arabs now view Russia as a more favorable ally than the United States and European nations, according to the 2018 Arab Youth Survey.

The survey, conducted by the consultancy firm ASDA’A BCW and consisting of 3500 interviews across 16 Arab States and territories, also found that young Arabs now consume more news online than anywhere else, including TV. More than half of respondents reported getting their news on Facebook daily, a platform where RT‘s has a larger audience than any other non-Arab outlet.

FALTERING WESTERN INFLUENCE

While its state-owned outlets have become a boon for the Kremlin’s project in the Middle East, the same cannot be said of the U.S. government’s Arabic-language outlets, which are increasingly viewed unfavorably in the region. “The problem is they have a bad reputation because they came with the U.S. invasion to Iraq,” a regional journalist explained, referring to the Alhurra-Iraq channel launched in 2004.

Created to counter Soviet propaganda during the Cold War, U.S. government-funded outlets are now ill-positioned to perform a similar role in countering Kremlin propaganda. Judged by the available metrics, Alhurraand Radio Sawa, the only U.S. outlets producing Arabic-language content, have such small online audiences as to render them virtually irrelevant.

According to Dr. Joe F. Khalil, Associate Professor in Residence at Northwestern University in Qatar’s Communication Program, “Alhurra now is trying to reinvent itself. What they’re trying to do is somehow move into more sensational… trying to capture audiences, because it didn’t register anymore on anyone’s radar.”

But the odds that these outlets can reemerge as trusted information sources seem uncertain at best. Kim Andrew Elliott, a retired audience research analyst for the U.S. government-funded Voice of America, noted that one of the primary factors in maintaining legitimacy in U.S. government broadcasting is the Broadcasting Board of Governors, an independent oversight body, which is “now in the process of being relegated to an advisory status and now it’s going to be a political appointed CEO” in the top advisory role.

“What will happen to U.S. international broadcasting now that it’s under this new political regime could be the end of the credibility of U.S. international broadcasting and it would take a very long time for that to be repaired,” he added.

Demonstrating the degree to which the rise of state-owned Russian media is exploiting and contributing to diminishing U.S. influence in the region, many of RT Arabic‘s top 100 most-watched videos cover developments in Iraq, the same country where Western coalitions led by the U.S. have spent staggering blood and treasure for decades. Notably, the popularity of RT Arabic‘s Iraq videos is supportive of the Nielsen study’s finding that RT‘s largest and most loyal audience is in Iraq, where the study claimed RT was viewed by 44% of the country’s population daily.

While the West has begun to grapple with the Kremlin’s project to spread misinformation and pro-Kremlin narratives via its state assets in the U.S. and Europe, Kremlin media continue, virtually unchallenged, to fan the flames of widespread anti-Western grievances accumulated after decades of U.S.-led wars in the Middle East and to leverage Russia’s growing economic and military influence to replace the U.S. as the region’s preeminent foreign power.

Elliot Stewart (@elliot_stew) is an Arabic-language media analyst living in the Middle East.