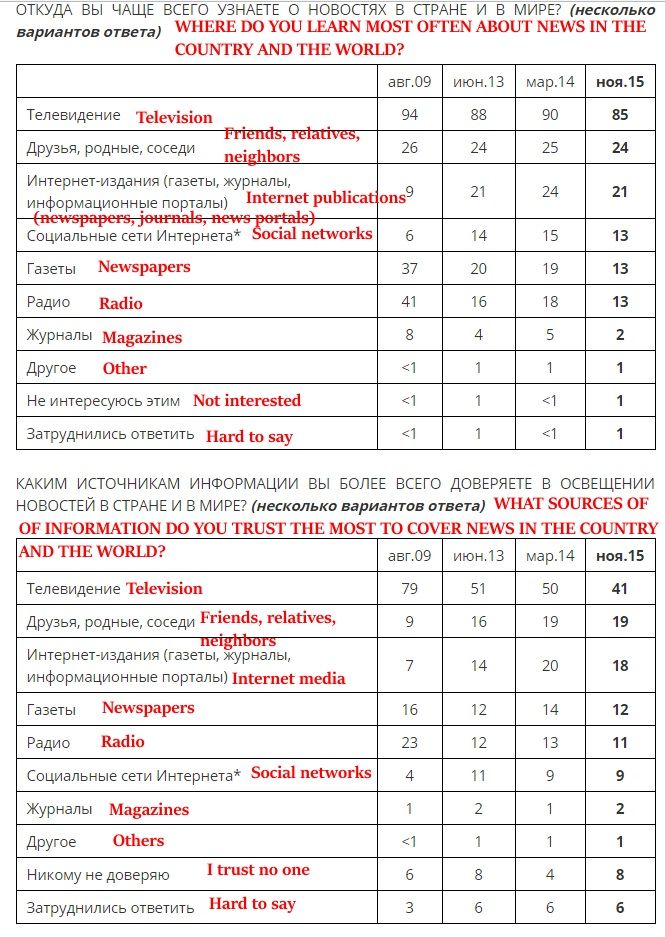

A recent Levada poll in Russia has found that most Russians, 85%, get their news from television stations, which are mainly state-owned or pro-Kremlin, but nearly half, or 41%, don’t trust the news they are getting.

Welcome to our column, Russia Update, where we will be closely following day-to-day developments in Russia, including the Russian government’s foreign and domestic policies.

The previous issue is here.

Recent Translations:

–The Non-Hybrid War

–Kashin Explains His ‘Letter to Leaders’ on ‘Fontanka Office’

–TV Rain Interviews Volunteer Fighter Back from Donbass

–‘I Was on Active Duty’: Interview with Captured GRU Officer Aleksandrov

UPDATES BELOW

With now 3,028 diverse entries, it is difficult to characterize the nature of most of the “extremist” materials emanating from every corner of Russia. But many of them seem to deal more with the extremism of Russian nationalism and fascism than with Islamism, and illustrate that it is often provincial courts addressing the problem of neo-Nazi youth rather than Moscow.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick

A gunman in an Infinity car drove by a parked car on Solyanka Street in Moscow and shot dead a man who was later identified as Mukhtar Medzhidov, 35, a former candidate for the parliament of Dagestan, Gazeta.ru reported.

The drive-by contract killing in the center of Moscow, following a gang shoot-out in a cafe earlier this week in which 2 were killed and 9 wounded, has residents worried that the lawlessness of the 1990s could be returning.

Translation: The murder in the center of Moscow was a contract murder.

The Investigative Committee has opened a murder case.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick

A recent Levada poll in Russia has found that most Russians, 85%, get their news from television stations, which are mainly state-owned or pro-Kremlin, but nearly half, or 41%, don’t trust the news they are getting, down from about 50% in 2009.

Another important trend is the sharp drop in Russians who get their news from the radio — 41% in 2009 to 13% today. The importance of radio in Russia, particularly in remote areas without good roads, was a factor in attracting listeners to foreign broadcasting. The Levada poll did not ask whether foreign news was a source for Russians, but the figure is likely to be low.

The poll sparked a debate on Twitter a US Embassy official in Moscow and his followers.

The Village, an independent lifestyle site, interviewed Lev Gudkov, director of the Levada Center, about the efficacy of propaganda in Russia.

Gudkov referenced the 19th century Russian satirical author Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who even before George Orwell wrote about the duality in people’s minds shaped by a repressive and undeveloped society. He pointed out that in 2012, about 45% of those polled had expressed support for opposition leader Alexey Navalny’s slogan that the ruling party United Russia was “a party of crooks and thieves,” but then support lessened and people forgot about it.

Asked if there was now a split in society over the annexation of the Crimea, Gudkov pointed out that the government’s step-up in propaganda began even before this in 2011-2012 with the protest against Putin, and “the anti-Western and anti-liberal campaign became the basis for the anti-Ukrainian wave of propaganda.”

Gudkov: It isn’t falling because Russians’ attitudes toward politicians is completely different. Politics is another plane of existence, that’s where the great past and heroic history are. Putin is an influential world leader in Forbes ratings. If you translate this from the international context to the domestic one, it turns out that Putin is the head of a very corrupt regime which did not obtain particular success either in the war on terrorism or the war on crime. The economy is failing.

The Village: But Russians don’t perceive him as the head of a corrupt, failed state?

Gudkov: Because their entire experience is the experience of the Soviet era, the experience of adaptation to a repressive state, the wish not to stick their heads out of their niche, take responsibility themselves for the state of affairs in the country and take part in politics and civic life. Therefore, the perception dominates of the leadership of the country as a completely different group of people living their own interests who can’t be influenced. The treasury is a bottomless barrel. Can you affect the making of decisions in Russia?

The Village pointed out that a whole new generation has now come of age since the failed coup in 1991 who did not remember the Soviet Union. How to account for the persistence in Soviet attitudes? Gudkov said that social institutions are more persistent than the changes in generations, and that they create a harsh sytem of rules that people submit to. The Village pointed out that many young people had come to the 2011-2012 protests.

Gudkov said that in fact most of the protesters at that time were people in the age cohort of 45-55, and only 12-15% of the participants were young people.

Really, the people who came out to protest were the generation of adult, educated people who had already achieved some social status and who realized that they were trheatened by another presidential term of Vladimir Putin. But the youth were fairly passive and uninvolved. All social changes began when youth becomes involved in civic life, but that doesn’t happen in our country: young people want to earn a good living and have a good time.

Asked why there were so few people willing to oppose the government in Russia, and whether it was because people simply didn’t want to think, Gudkov replied:

Yes, because thinking is dangerous. This is not current fear, this is not born from the sufferings of recent years. This is a petrified, accustomed fear coming from the Soviet or even earlier time. If this knot is unwound, the picture is rather complex.

Let us start with the fact that all conversations about perestroika, about how we had a revolution in 1991, from my perspective, do not hold up to any criticism.

The basic institutions which ensure the structure of society did not change so radically. What changed most strongly, of course, were economic relations. To some extent market mechanisms were established, although now there is movement backward. Let’s say in 1991, after all the reforms, the state controlled a little more than a quarter of assets. Today, it controls almost 60%. That is, the share of the government in the economy has grown sharply, and accordingly, the government bureaucracy and what is mistakenly called the middle class in our country. Even so, it’s not a planned economy, but a kind of version of state capitalism with elements of a market economy.

The system of communications, including purely technically, have changed. Things have appeared that didn’t exist before — mobile telephones, Internet. Mass culture changed — it is not censored as in the Soviet era, no on tells you what to publish. I don’t mean the mass media, there the censorship has been restored in full. Although it is not as total as it was in the USSR.

Most changed is mass consumption, we have revolutionary changes in that sphere. But the structure of government and the institutions on which is relies, that is the courts, the legal system, the law-enforcement agencies, the army and educational system remained practically unchanged. The signs have changed but the construction of government uncontrolled by the people has been preserved in full. That is why the backsliding is happening so easily now, that is, the reproduction of Soviet practices.

Gudkov then explains how it is that most people can get all their news from state television and distrust it — but go on supporting the government.

Propaganda works thanks to three very important conditions…One is the turning of attention from everyday issues to mythological issues. But for this shift to occur, two other factors need to be present. That is the creation of a sense of growing crisis in the country, that we are approaching a disaster. Such an atmosphere leads to the appearance of fear and lack of confidence in society.

Propaganda systematically produces such situations — if only by the fact that many issues are simply not discussed. The government makes decisions without explaining them or notifying people. Therefore people are always in a certain state of expectation: now the prices will go up and the age for pensions, housing costs will rise, paid parking will be introduced. There’s a sensation of chronic vulnerability, defenselessness before the government and any of its decisions, and this creates a chronic background of alarm and expectation of nastiness. Another condition is the discreditation of any official sources of information — no one can be trusted, they’re all worms.

A person is in a state of confusion — any position departing from the official one is placed in doubt. And what can a person say about what happened in Ukraine, on Maidan or in the Donbass if he gets all information exclusively through the box? He only knows that prices are going up because he checks that himself, but what can he know about the mistreatment of [Russian] adopted children in America [a staple of state propaganda–The Interpreter]? He should either believe or not believe, he can’t check it. As a result there is a sense of half-trust in society, half-disbelief, and that everyone is lying.

Asked how many Russians sought out alternative sources, now that 55% are reported to have access to the Internet, Gudkov said that 1 to 1.5 percent only.

The poll was taken in person house to house from November 20-23, 2015 from a representative sample of 1,600 people age 18 or older in 137 towns, with a margin of error of 3.4%.

— Catherine A. Fitzpatrick