Readers of this blog may have heard of the Center for Eurasian Strategic Intelligence (CESI) that seems to promote a “hawkish” view on Russia’s foreign policy. In his Twitter, Edward Lucas has recently raised doubts about the authenticity of this organisation, and, as I found out, for a good reason. Let’s have a closer look at CESI.

(Note that I will not be discussing their analyses, as they tend to plagiarise from other sources.)

Major resources of CESI:

– Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/eurasianintelligence. Registered on 18 March 2014.

– Website: http://eurasianintelligence.org. Registered on 18 July 2014.

– YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/eurasianintelligence/ Registered on 6 August 2014.

– Twitter: https://twitter.com/EurasianIntel. Date of registration unknown, first tweet on 12 August 2014.

(The first two dates: This may be just a coincidence, but on 18 March 2014, “Republic of Crimea” and the Russian Federation signed a “treaty on accession of the republic of Crimea to Russia”, and, on 17 July 2014, the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down by (pro-)Russian right-wing extremists in Eastern Ukraine).

According to their website, CESI “provides analysis and surveys of political, economic and security processes in Eurasia region. CESI was founded in 2014 with a focus on Russian policy of expansion and military aggression in the Eastern Europe”. It lists the following individuals involved in the workings of the organisation:

– William Fowler, Chairman and CEO

– Alex Kraus, Chief Analyst

– Kelly Hunt, Chief Operating Officer

– Steven J. Hudson, Chief Geopolitical Analyst

– David Carpenter, Chief Economy Analyst

– Gareth McCallister, Jr., Information Supervisor

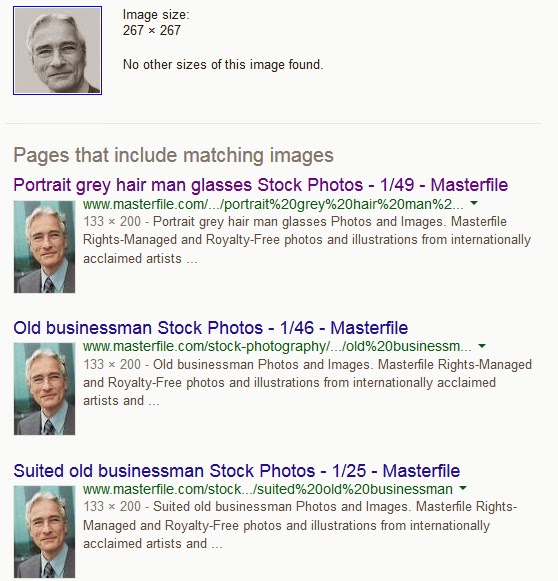

As Edward Lucas pointed out, William Fowler’s profile picture in his Facebook is a picture of an anonymous “old businessman with gray hair and glasses”.

An image search on Google

Thus, Fowler’s Facebook is, at the very least, misleading. Moreover, it is unlikely registered to any “William Fowler” at all. Most likely, the real name of the registrant begins with a “t” and ends with a “y”:

So, is “William Fowler” a real person? I doubt it. And I even doubt that anyone mentioned as a staff member of CESI is a real person. (I will not go into detail with every person mentioned as a staff member of CESI, but I would invite the interested readers to do so.)

The only member of CESI with a “face” is Alex Kraus.

A screenshot from one of CESI’s videos

Alex Kraus is the only person from CESI who appears in their videos. His native language is not English and he pronounces Russian names with a Slavic (i.e. close to Russian, yet not exactly Russian) accent. Kraus may be a Czech; at least he mentions his proficiency in the Czech language on his LinkedIn page.

A screenshot from Alex Kraus’ LinkedIn page. Note that his profile photo is not professional, but rather a screenshot from a CESI’s video uploaded on YouTube on 12 August 2014, the date when CESI posted its first Tweet

CESI’s website is registered in the name of Abigail Kalopong, and she is probably the most interesting person in the whole story.

According to her LinkedIn page, she is a “nominal director” of CESI:

A screenshot from Abigail Kalopong’s LinkedIn page

Note that “nominal” is a key word in the story.

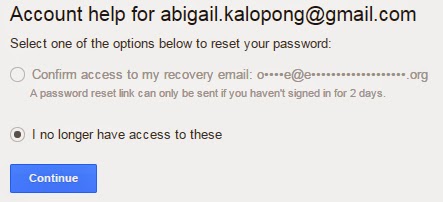

A national and resident of Vanuatu, yet most likely a real person. She controls a Twitter account of CESI –

– while her Gmail account (abigail.kalopong@gmail.com) is linked to CESI’s official e-mail address (office@eurasianintelligence.org):

Another interesting thing about Abigail Kalopong is that, apart from being a “nominal director” of CESI, she is currently a director of 59 companies!

If you add companies registered in the name of Abigail Kalopung, you will have 86 companies in total.

Almost all her companies are registered with one and the same address (which is actually a mailbox): Office 11, 43 Bedford Street, London, United Kingdom, WC2E 9HA. If one looks at the companies that are registered with this address, they will see that all these companies are “offshore-type” businesses. Moreover, those are largely connected to companies in Russia and Kazakhstan, as well as those associated with the regime of former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych and other Ukrainian businessmen.

Just a few examples concerning the Ukrainian connections:

– Kalopung’s Fineberg Limited seems to own a yacht named “First Wave” that apparently belongs to Serhiy Arbuzov, chairman of the National Bank of Ukraine and, later, interim prime minister under Yanukovych;

– Kalopong’s Helix Capital Investments Ltd. is a typical pyramid scheme that operates in Ukraine;

– Kalopong even “set up” a company named “Roshen UK Limited“, most likely to “squat” the name of the Ukrainian company Roshen in the UK;

– around 75% of the Zaporizhia Automobile Building Plant is allegedly owned by three British companies, of which two are directed by the same Kalopong, but, eventually, are most likely owned by some Ukrainian or Russian businessmen.

It should now be clear that Kalopong/Kalopung is simply a front-woman whose name is used to conceal real owners of the businesses she allegedly manages.

The same is the case for the “think-tank” CESI. What I do not know is who is the ultimate owner of CESI, but most likely they are either Ukrainian(s) or Russian(s).

At the first glance, the website of CESI seems to be anti-Putin, as it presumably aims to show the threats that Putin’s regime poses to Western democracies. However, a more nuanced analysis would probably show that the aims of CESI are very different. To fully understand these objectives, I suggest reading The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss. In this report, the authors, in particular, argue that one of the strategies of the Kremlin’s foreign policy is a reversal of “soft power”: Putin’s aim is not to be attractive, but to present himself as a bogeyman.

CESI pictures Russia as an immediate threat to the West, but it does so in a manner that exaggerates the threat in order to discourage the West from opposing the aggressive politics of Moscow and impel to appease Putin’s Russia at all costs.